We couldn’t let this one slide.

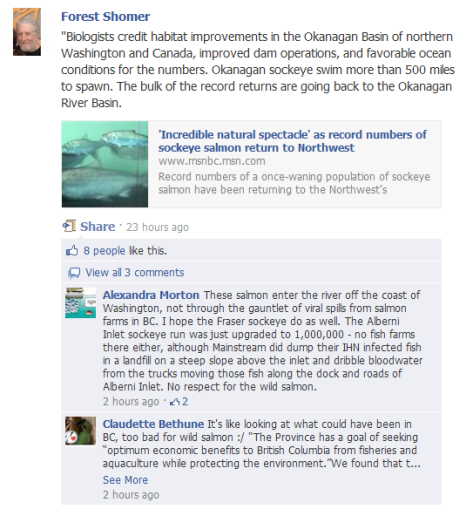

We found it on the public “Salmon are Sacred” Facebook page. This claim is integral to Ms. Alexandra Morton’s pet theory that the only salmon doing well in returns and on the spawning grounds are the ones which don’t migrate past salmon farms.

This is bunk.

There are numerous salmon farms in Puget Sound, which Washington fish pass on the return to their spawning grounds. One of them, the Bainbridge Island farm, is the farm which suffered an IHN outbreak in May. And there are three salmon farms in the Alberni Inlet. We checked, and they were in operation in 2010, when the sockeye run was 1.1 million fish in the Inlet, far higher than expected. The wild fish in these areas are doing fantastic; the salmon farms do not have any impact on the wild runs.

Here’s a picture. Click to view the full image, it’s a big one.

If you want to look for yourself in Google Earth, here’s a placemarks file you can use to find these farms.

Click here to download the placemarks file.

It is completely wrong for Ms. Morton to say that fish migrating up Alberni Inlet, along the south end of Vancouver Island, and into Washington State rivers, do not pass salmon farms. There is absolutely no truth to this claim.

salmonfarmscience says,

“Virologists involved in aquaculture science agree that for a farm to produce enough viral particles to spread into surrounding waters, there would have to be an extremely serious fish health event at the farm, i.e. 30 per cent of the fish dead and sunk to the bottom of (sic) floating on the surface. This has not happened at any farms for at least a decade.”

Note: 30% is exactly the die-off that historians tell us the industry experienced previously.

I find it alarming that the industry believes that unless there is massive die-off on the farms, the wild salmon are safe. My understanding is that this might be true if the species farmed is the same as the species affected. Immune compromised farmed salmon (crowded, randomly mated, low omega3 diet, etc.) would likely die before they killed wild salmon. But since, with fish farming, the natural host/prey dynamic is altered–farmers can either replace dead fish or control numbers by changing where and when they raise their fish–I’m not sure even this is true,

When we consider disease transmission between different species of salmon as we are doing here, things are even less simple; many viruses are more or less virulent depending on the species of salmon they infect. Some viruses can be carried and amplified in one species (IHN in chinook for example) with little affect (disease) to the chinook but they can do great damage when transmitted to another species (IHN is not known as “sockeye disease” without warrant). This occurs often when the species are far apart (sea lice, for example, when they act as vectors for disease don’t necessarily die) but can occur with species that are close together (sub-species, in fact). Much harm, seems to me, possible, even when the fish on the farm don’t die.

What am I missing? Which virologists make this claim?

It looks like you meant to comment on a different story, this one doesn’t have any of the quotes you reference, but that’s OK I remember writing them.

The comment about virologists is from a conversation I had with Dr. Kyle Garver, the current leading expert on IHN in BC, possibly the world. This was also the view shared by his predecessor at the Pacific Biological Station, I have been told.

What’s your source for what “historians tell us” was previous die-off? The only example I can think of is the catastrophic IHN infection incident in 2001-2002. And that was all in a very short period of time.

It’s not what we believe, it’s what the science shows us. Again, as modelling and mathematical studies by virologists have shown, in order for sick farmed salmon to create enough virus to pose any threat to passing migrating salmon, they would have to be experiencing a catastrophic fish health event, with 30% of the fish left in the pens sick and dying for an unusually long amount of time. This does not happen.

I’m confused about your comments about IHN and Chinook. It’s sockeye that naturally carry this virus, typically with no symptoms.

Finally, there’s one big difference between the health of farmed and wild salmon. Our fish are vaccinated against the most common diseases they encounter in the ocean. This greatly reduces any viral load they may be carrying, and viruses cannot thrive in vaccinated hosts.

The greatest risk of passing viruses and diseases to wild salmon is other wild salmon, not farmed salmon, which they rarely encounter, and which we must keep healthy through their 18 months of life in the ocean.

A classroom full of immunized, healthy children does not pose a risk to a few visitors who are only there for a day or two.

Hmm.. All this protestation. Maybe we should take a closer look. First, do I have the history of chinook salmon aquaculture in BC right?

In 1985 fish farms started in Sechelt Inlet using the only fry that were available, namely coho and chinook from dfo’s Salmon Enhancement Program (SEP). So at the start, 100% of farmed fish were coho and chinook. By 1989 the percentage of farmed salmon that were chinook had declined to 77% (Atlantics were making inroads), by 1992 only 57% were chinooks, by 1995, 33%, by 2002 it was 14%, and today they are at about 6% of total production. As their percentage of total production declined, chinook farms also moved, first out of Sechelt Inlet because of algae blooms and disease, then to the “outer” waters of Johnston and Queen Charlotte Straits and finally, because they were still experiencing die-offs, to the west coast of Vancouver Island. According to David Conley, (Salmon Farming in British Columbia: Industry Evolution and Government Response, 1997),. During this “rationalization period”,

“Diseases, such as Bacterial Kidney Disease (BKD), vibriosis and marine anaemia, took a large toll during this period. Attempts to maximize capital investment by holding fish at high densities only served to maximize stress for the Pacific salmon, resulting in severe disease outbreaks. The industry averaged losses of 30% of its production per year and some farms suffered losses as high as 70% in a given year. Handling and grading also brought on outbreaks of disease.”

“Farms continued to refine their Chinook culture strategies but these operations relocated to the west coast of Vancouver Island where conditions appeared to suit this species.”

So generally, the picture is that the number of chinook salmon farmed in the migratory route of Fraser sockeye declined continuously for the last 20 or so years. It’s true, there were two remaining farms in 2008, but one can’t be serious to imply they could keep Fraser stocks depressed in 2010: the Yellow Island farm is the smallest farm in BC (100 tonnes) and maintains low densities; the Middle Bay Salmon farm didn’t produce adult fish until 2010 (and even these were harvested premature). It is closed containment and therefore like the Yellow Island farm has little benthic impact (accumulation of feed and feces beneath farms is often cited as a contributing factor to disease by producing anaerobic conditions conducive to viral growth).

Overall then, the bigger story here is that there has been a war between farmed chinook salmon and wild Fraser sockeye (I admit, this is just a story… maybe we should look at what’s happening in Clayoquot Sound, where the chinook farms are now, to see if it’s a good one). Every chinook farm placed in the migratory route of these sockeye experienced such severe die-offs that they were forced eventually to move to places where there aren’t many returning sockeye (plausible? The industry readily acknowledges that diseases pass from the wild to the farmed, sometimes the effects must be severe–see mortality curves and transmission pathways in, for example, Sonya Saksida Investigation of the 2001-2003 IHN epezootic in farmed Atlantic salmon in British Columbia).

So all the large high-density chinook farms retreated, they weren’t economically viable where they were. Really, in a way you could argue that the wild sockeye cleared the chinook salmon farms out of their own migratory route. And now the sockeye can do better.

The industry is not pleased with this picture; if the sockeye were to rebound when the farms are gone, it might not look good for them. They poke at this history with suspicion. And yes, they’ve discovered a glitch. “Not so fast.” they argue, “How do you explain the low returns of 2009, if you think farms are the problem? There really weren’t enough farms in 2007 to explain the low 2009 returns.” What about that, eh? Everyone chimes in with,

“There was one active farm with Chinook salmon on the wild salmon migration route on the east side of the Island in 2007. Apparently this is enough for Ms. Morton to blame it for causing the 2009 decline. Yet she is wrong about this point too.”

But this one active farm is no ordinary farm. Early in 2007, during the Fraser sockeye out-migration, the Conville farm situated in Hoskyn Channel on the east side of Quadra Island–a particularly dangerous location to Fraser sockeye, was full of adult chinook salmon. Samples taken from the farm that year were reported to have symptoms that are often associated with clinical diagnosis of marine anemia. (Cohen Commission Transcripts, Sept 7). This farm is on the main migration corridor, on the pinch point in fact. It is not unreasonable to suggest that it could have a large impact on Fraser sockeye. Of course, what with all the variables at play, one year doesn’t tell us much, still it’s just what viruses are capable of–ask any fish farmer.

What we might be witnessing is a remarkable (and improbable) victory for wild salmon. The Conville farm, fallowed later in 2007, was the chinook farmers’ last stand.

Usually the outcome will not be this happy; farms will decimate wild stocks and even though the farms will also sustain some losses, the farms will be restocked and now the fewer wild fish will have less effect on the farms. The farms will win (Neil Frazer explained this well). Still maybe for now, and only with respect to salmon anemia and chinook farms, the wild salmon can claim, “We won!”

A bit like the few remaining warriors after an epic battle, surveying the fields knee deep in the corpses of both foe and dear friend… searching to find some solace.

Thank you for sharing this. However, you miss some critical points and err in your analysis of the Conville Bay farm.

There was nothing unusual noted there in terms of fish health. If there was nothing unusual, there would be no significant amount of viral particles to affect wild fish. Virologists involved in aquaculture science agree that for a farm to produce enough viral particles to spread into surrounding waters, there would have to be an extremely serious fish health event at the farm, i.e. 30 per cent of the fish dead and sunk to the bottom of floating on the surface. This has not happened at any farms for at least a decade.

Even if a few fish at a farm are found to have died from something like marine anemia, the risk to wild fish is negligible unless a catastrophic amount of farmed fish are dying from the disease.

And farming practices today make this extremely unlikely. For example, in the recent IHN “outbreak” only three farms were affected, and each was considered to be an index case (they did not spread to any other farms). In all cases fish were removed from the water quickly before a significant amount of fish even showed signs of disease. There simply were not enough viral particles in the water to pose any threat to passing wild fish (fish which already carried the virus naturally).

Also when looking at the trends over time you must consider ocean conditions such as the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, food availability in the North Pacific, competition with billions of ranched Alaskan salmon and ocean acidification.

People like Morton ignore the bigger picture and focus on things like salmon farming, which do have some impacts, but such small impacts that in the bigger picture it’s microscopic.

It’s like arguing about how many angels can dance on the head of a pin.

I looked at the Government data on salmon farm locations in the Wild Salmon Narrows. I count over 46 farm sites the Pacifics pass. On your location map supporting you theory I count 4 farms in the migration path. What is the total Atlantic salmon count between the two passages? The farm count alone is running over 11 to 1!

You know what they say about figures.

Ms. Morton says there are no farms in the Alberni Inlet. We showed there are three. Morton says there are no farms on the south end of Vancouver Island. We showed there are farms in Washington.

She is wrong, and her theory that certain runs that migrate on the outside of Vancouver Island are doing better because they don’t pass salmon farms is wrong.

That said, you make an interesting point. Yes, there are more farms on the inside of Vancouver Island. However, Ms. Morton has made it clear she believes that justone farm is enough to kill tens of millions of sockeye migrating past them and blames one farm in 2007 for causing the 2009 Fraser sockeye decline:

There was one active farm with Chinook salmon on the wild salmon migration route on the east side of the Island in 2007. Apparently this is enough for Ms. Morton to blame it for causing the 2009 decline.

Yet she is wrong about this point too. Because in 2008, there were two other active Chinook farms in Discovery Passage, one on the west coast of Quadra Island, and the other, Agrimarine’s “closed containment” farm in Middle Bay (which still allows sea water to pass in and out of the tank, offering no “closed containment” for viral particles).

Ms. Morton is grasping at straws, anything she can possibly find to fit her pet theory that fish passing salmon farms die. There is simply no real-world evidence to prove this.

Some not so convenient research for the sacred salmon folks, published in Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Science yesterday. Productivity of sockeye has been falling on an adults returning per spawner basis across a large geographic area, and over a long period of time. Based on their time series analysis, they come to a conclusion that whatever is driving the declines must operate over large geographic areas, and must be persistent historically and increasing in intensity with time. The data spans from 1950-2004.

Though it’s interesting to note that the decline is common amongst the sockeye stocks within the range from Puget Sound to southeast Alaska, the effect is opposite in sockeye stocks from central and western Alaska. I can’t help but wonder if there is a hatchery effect in this data as well. If I’m not mistaken hatchery ranched salmon make up the lions share of the total catch in Prince William Sound, central Alaska.

Though it could be another case of fun with graphs for the sacred pseudo-science crowd. The decline starts at about 1985. Same year that New Coke was introduced by Coca-Cola. Coincidence. I think not!

Okanagan Sockeye are doing much better, but what is not mentioned in the Sad and Silly facebook page is that hatchery enhancement has likely played a role in that success also. I notice that Morton is still confused about IHN.

When I see stuff like this I keep thinking of an old SNL skit called “Brian Fellow’s Safari Planet” for some reason.

What, Ms. Morton distorted facts? Again? Say it ain’t so …

FWIW, it seems the media are perhaps tiring of her rants as she has had a bit less press lately. Go away Alex and put your obvious passion and zeal to good use by fighting a real cause of wild salmon declines.

For clarification ,the farms in the alberni inlet system are at Jayne Bay, San Mateo Bay and accross from the coulsons millsite near Nahmint. I believe the site at Nahmint is no longer there yet was in 2010. San Mateo is a smolt site with low biomass but is active throughout the wild salmon migration period Jayne Bay site is a full production growout site that has been there about 20 yrs. Strong return of sockeye expected this summer.

You are correct, but you may be thinking of the old Penny Creek farm site near Nahmint. Mainstream Canada used to operate that site but from what we can tell they no longer operate it. San Mateo is a lens site (used for saltwater entry) and Barkley is a site used for smolts and small fish as well. But they are still salmon farms, and are still active.