We’ve had a lot of fun with Ms. Alexandra Morton’s ridiculous use of one particular graph to claim that salmon farms in BC brought about a decline in wild salmon productivity.

Without any context, her argument sounds reasonable.

But in context, it all falls apart as we showed in an earlier post and again in this post.

Recently, DFO released its 2012 projections for Fraser River sockeye, estimating a 90 per cent probability of a maximum run size of 6.6 million.

Their predictions are summarized in a graph, including an estimate of the productivity of this year’s run, placing it just above the average.

This is, incidentally, the same graph Ms. Morton uses, but with all the context included.

See that? 2012 will likely be an average year.

What does that mean?

It means Ms. Morton’s predictions of doom and gloom are, once again, false prophecies.

Salmon runs fluctuate, and have done so ever since we started recording these numbers half a century ago.

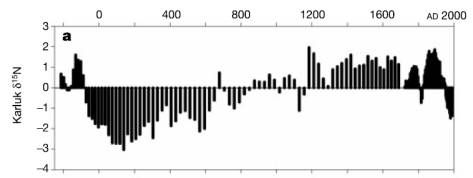

In fact, according to recent research in Alaska, salmon runs have fluctuated for more than 2,000 years.

Humans have been impacting Fraser sockeye stocks and the stocks of every other kind of salmon in B.C. for thousands of years, and our impacts have increased ever since we started catching salmon in massive amounts and damaging their habitat more than a century ago.

But it seems apparent that ocean conditions have far more long-term impacts on salmon.

But Ms. Morton and anti-salmon activists don’t care about those facts. They focus on a small window in time and on one river system, asking, why did Fraser sockeye productivity decline for roughly 20 years starting in the 1990s?

It was salmon farms, they say, answering their own question and fingering the “new kid on the block” before anyone can raise any other possibilities or use science.

In contrast to their easy answers to hard questions, a scientific approach requires we look at as many possible factors as we can find.

What did cause the decline of Fraser sockeye productivity in the 1990s and 2000s?

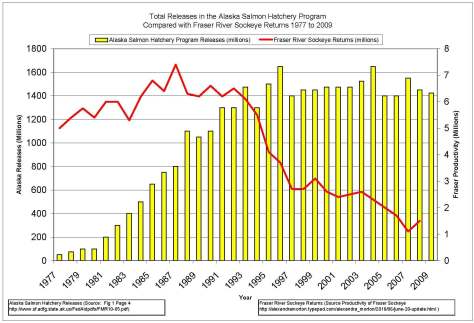

Was it an explosion of Alaskan ranched fish entering the North Pacific feeding grounds in the early 1990s? Take a look at this graph.

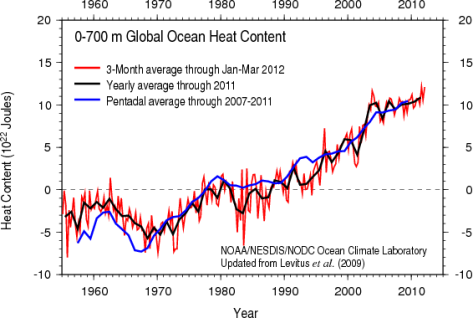

Was it ocean temperatures? The ocean has gotten hotter since the 1950s. Interestingly, the decline in temperatures in the 1960s could be correlated with the dip in Fraser sockeye productivity at the same time. But the rise above average (0) since about 1990 can also be correlated with the decline in productivity in the 1990s and 2000s.

Was it The Pacific Decadal Oscillation? The natural fluctuation of ocean temperatures, which changes every 15-30 years? Interestingly, the brief change in the 1960s can be correlated with the decline in Fraser sockeye productivity at the same time, and the major shift from a long-term trend in the 1970s and 1980s to quick fluctuations in the 1990s and 2000s can be correlated to the long-term stability of Fraser sockeye productivity in the 1970s and 1980s, and the wild fluctuations and decline in the 1990s and 2000s.

Was it any of these things? All of these things? None of these things? We don’t know. We haven’t even included catch data in this post, that has to be considered as well. But it sure looks like ocean conditions have way more impacts than a few salmon farms ever could.

Plus, there is actually evidence to suggest that ocean conditions do have impacts (in contrast to the speculations and simplistic correlations anti-salmon farming activists use to support their claims).

But we can’t say for sure.

One thing we know for sure, however, is that, given all these factors which could affect Fraser sockeye productivity, suggesting that “salmonfarmsdidit” is a facile conclusion to the mystery, especially when we don’t even have a body.

The “corpse” of wild salmon is still swimming strong, despite all the predictions of doom and gloom, and with an average run predicted for the Fraser, exceptional runs predicted for the Alberni-Clayoquot region and good returns expected elsewhere in BC, we are confident in saying that all the evidence shows that wild and farmed salmon can coexist together in the same ocean with negligible risks to either species.

Farmed versus wild is a false choice.

Choose both.

From the Marine Harvest we site http://www.mainstreamcanada.ca/mainstream-canada-farm-north-tofino-tests-positive-ihn-virus-0

Ok I repeat myself.”lets test all the farm sites and get the real story”! Morton may be doing bad science but you are doing NO SCIENCE! 25 Pacifics in a tank with 10 infected Atlantics and a hypothesis carved in stone becomes the truth for the entire Wild Pacific Salmon population

All things are true about the null set. We can’t see Kibenge’s data, so there’s no telnlig what she actually found (or didn’t find). It’s entirely possible that her Canadian colleagues had excellent reasons for disputing her results. It’s also entirely possible that they’re covering something up. I don’t think it was productive for Kibenge to go to the media with this, though. Now we’re faced with lots of speculation without any new data.

Sturgeon fishing has been very good thourghout the Fraser river from Yale to downstream of Chilliwack!! Lots of medium sized fish just under 100lbs with a few over 200lbs thrown in the mix. Plenty of bites to keep you watching as well.Expect a big one to come out in the next couple weeks!

Fair comment:

But the evidence of the Cohen Commission is that the regulators are more focussed on property rights than striking a balance between private property rights and common property resources.

And, in the west coast, marine spatial planning is not central to any marine planning whether it is oil tanker routes or spatial distribution of farmed salmon.

We will just have to wait and see what Justicce Cohen says.

-88-

That’s not what we got out of the Cohen Commission, but fair enough.

Quote: “See that? 2012 will likely be an average year.”

Well, we all hope so, but forecasting Sockeye isn’t a perfect science. As the document explains, forecasts are highly uncertain due to variability in survival rates from egg to adult life stages. One of the best documents I have found to date which really puts forecasting into content is this:

Click to access Peterman2008-Pre-seasonForecasting.pdf

I highly encourage pro or anti-fish farm types to read this. It will help people understand that forecasting is not an easy job.

I disagree that all wild salmon stocks are strong. For instance, Upper Fraser Chinook are not doing so well these days – requiring some unpopular allocation restrictions to recreational fishermen. In addition, most Fraser Sockeye CUs are either in the yellow or red. I realize that you attempting to counter the doom and gloom arguement by opponents and I agree with that to some extent, but I still think we need to be somewhat realistic about what we have right now. Yes, runs fluctuate, but I believe we are encountering some unusual prespawn behaviour these days. However, I do not believe that these declines can be attributed to BC fish farms with the present information we have to date. Morton’s approach picks out certain pieces of evidence, but greatly ignores other evidence. She understands Orcas, but not Sockeye. The document produced by the BCSFA clearly outlines some of the holes in her arguements (but there are many other holes).

As your graphs indicate, there is other compelling evidence that could explain these declines. Forecasting attempts to incorporate these environmental variables, but it is still extremely difficult. We really need to look more at the wild fish and the impacts on survival of the diseases as well as the early marine life of juvenile salmonids. To date, fish farms and hatcheries have accumulated most of this knowledge regarding viruses and diseases.

Very good point Steve. The DFO report we linked provides extensive details about how they predict salmon returns. The mathematics is mind-boggling, and people need to give them some leeway and not expect predictions to match up with reality. No one expects that of the weatherman.

Also we didn’t mean to give the impression that all salmon stocks in BC were strong. Some are doing well, some aren’t. In general though, they seem to be doing well.

Interesting point about prespawn mortality. According to studies from 30 years ago we have read from the Pacific Salmon Commission, this has been a concern for a long time. We need to do more research on it but it doesn’t appear to us that there is too much of an increase in prespawn mortality, at least not enough to be significant.

We do need to research this more, however.

Prespawn mortality is not a new issue. I mean there is and there always has been a component of the run that either dies enroute or on the spawning grounds before spawning. Typically this prespawn is seen in the front end of the run.

I realize that there very well could be reports out there about prespawn mortality. However, what needs to be understood also is that spawning ground data collected 30 or even 20 years ago may or may not be comparable to what we collect now. There can be gaps in it a dataset time series due to environmental conditions (i.e. fence could have been blown out or visual surveys couldn’t be conducted due water clarity), the number of surveys conducted (i.e. 4 day cycle, 7 day cycle, or only once), when surveys were conducted, and methodology. The reliability of that data can be suspect.

It is not that people were doing something really wrong 20 or 30 years ago and that their data is crap, but nowadays field crews that conduct escapement surveys are better trained with much more refined methodologies to conduct surveys. It also depends whether a particular study area includes or doesn’t include prespawns in the estimates. I believe crews are more cognisant to look for prespawn mortality nowadays. I think the public is more aware also. Good seasonal field personal is retained year after year making for better data quality (IMO). In addition, crews also have much better equipment (i.e. boats, rafts and fence materials) to access areas that they had difficulty in the past.

I agree we need to do more research on this because it is not so cut and dried as anti-fish farm people make it out to be. For instance, if farm critics go out side of Morton’s blog to actually learn something about Harrison Sockeye they will find that Morton’s theories do not hold true. Lastly, I also do not think Mission should be taken as gosphel either. There are inherent issues with counting digital fish in the Lower Fraser as well as with stock identification. We need to continue to support good stock assessment on the grounds.

The Sockeye is a salmon we don’t find in Stoney Creek. Sockeye are blue tgeind with silver in color while living in the ocean. Just prior to spawning both sexes turn red with green heads and sport a dark stripe on their sides. Males develop a hump on their back and the jaws and teeth become hooked during their move from salt to fresh water . (wikipedia) Here in Burnaby: In 2009 there were Chum and Coho as far up the mountain as tributory 3A and even Chum and Coho fry found in upper reaches never found with salmon before. There were smaller returns of Pink Smaller found as well in Stoney Creek, closer to Lougheed highway. (Stoney Creek Env Committee)The Sockeye return in the Fraser is great news as we have suffered unusual low returns in the last 3 years.The spawning lifespan for the Sockeye is generally 4 years.There are broad terms we can approach the salmon from cultural to global warming to inter-relations of salmon and predator species of the salmon. Many groups are competing for the waters needed for the fish groundwater wells effect quality, small hydro plants, and there are many impacts at sea including ocean warming, fish farms etc.The greatest lesson I take away from the sockeye is the cloud of information around their numbers. There are so few factors we can be assured. I highly recommend reading the report from the Sockeye Symposium -link found below. For people with a curiosity it offers insight into the science and the issues. It is a fascinating read. To have such wildlife so close to home is a blessing. I am also heartened to experience the ability of my human neighbours to appreciate the nature.Thanks Lois.Hope is not so far from us here in the GVRD. Eh?Vivian S.UNES

You may have missed the point of some of Ms. Morton’s comments.

Both in Norway and in BC, there are good and sound arguments and science that the way for both the farmed salmon and wild salmon to co-exist, is to remove heavy concentrations of farm salmon from migratorywild salmon pathways.

What was not obvious when the salmon farms were located in BC is that the farmed fish pens provide single species vectors for virus transmission and sea lice concentrations.

The Norwegian marine regulators are alert to these dangers (according to the Norwegian auditor general in 2012) and ensure that there is a marine spatial planning strategy, a marine biosecurity policy and separation of the farm and wild fish.

Why not the same in BC?

And yes, the Norwegian government also recognizes the other factors such as ocean temperature rise, ocean acidificatiion etc but a central policy direction is preservation of wild salmon stocks, and preservation of aquaculture economics by prudent use of science and marine planning.

-88-

You may have missed the point of this post.

The point is, given the massive ecological forces at work in our ocean, ignoring those factors and the science tracking them and blaming salmon farms in B.C. for all the woes of wild fish is short-sighted, facile and pseudoscience. Ms. Morton’s sole focus is to get rid of salmon farms. We see nothing in her writings that suggest otherwise.

To your other points:

The Pacific Northwest is very different from Norway.

In the Pacific, the wild salmon stocks are strong. The majority of salmon being farmed in B.C. are Atlantic, a different species. Risks from interactions between wild and farmed are low, because the Pacific salmon species are well-established and stocks are generally healthy.

In Norway, and most of Europe, Atlantic salmon have been heavily fished out over centuries. Risks of interactions between wild and farmed are high, because they are the same species, and because the stocks of wild salmon are not generally healthy.

Here in Canada, DFO’s role is very similar to the Norwegian government, as you describe: recognizing “the other factors such as ocean temperature rise, ocean acidificatiion etc but a central policy direction is preservation of wild salmon stocks, and preservation of aquaculture economics by prudent use of science and marine planning.”